Some television moments don’t just make you laugh. They feel dangerous, like something might actually snap if the scene goes on a few seconds longer. One of the finest examples comes from Fawlty Towers, in an episode that quietly stages one of the greatest clashes of personality ever filmed inside a seaside hotel.

It begins, as many disasters do, with a polite request.

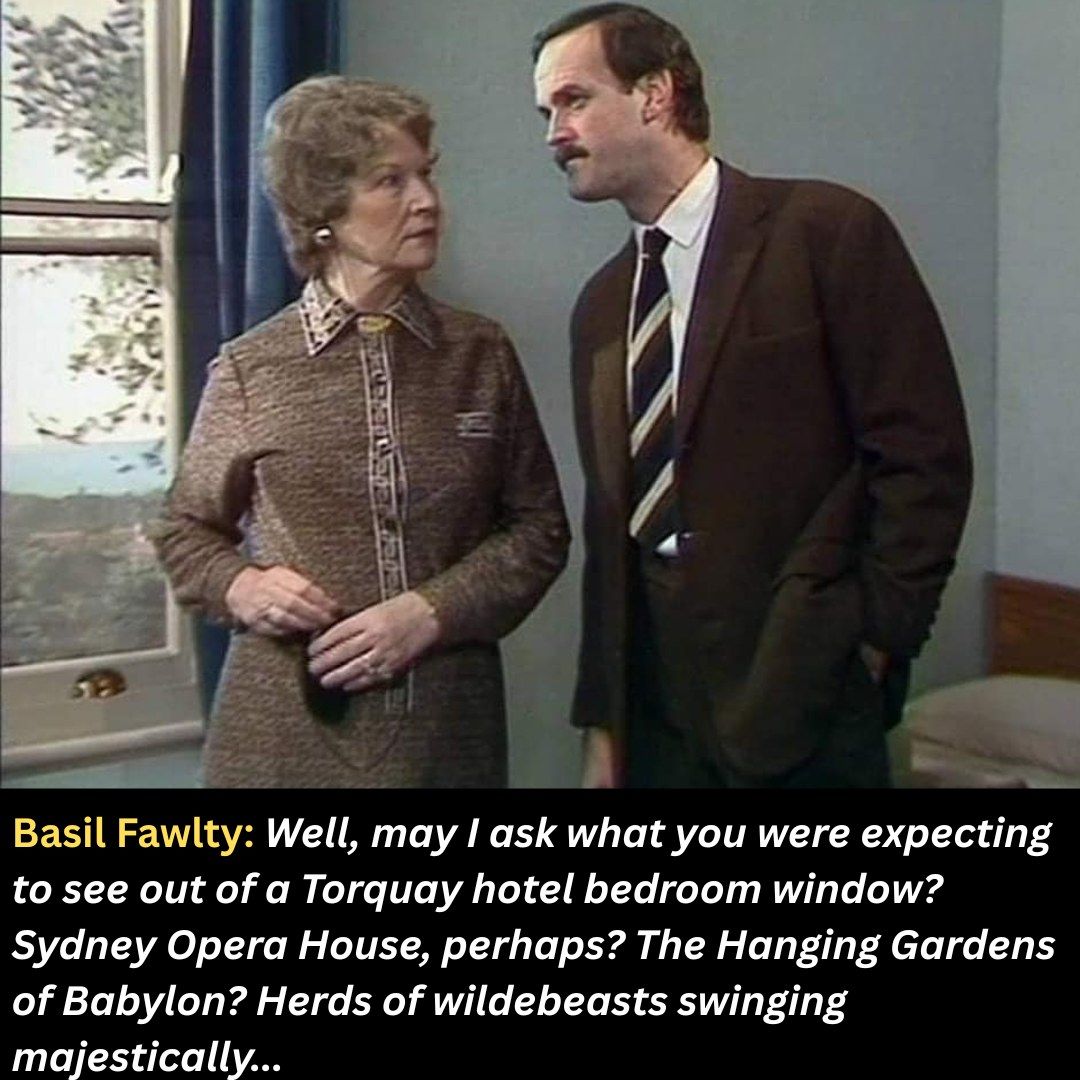

Mrs Richards arrives at the Fawlty Towers in Torquay expecting a “room with a view.” On paper, Basil Fawlty has delivered exactly that. Outside the window is Torquay itself — grey sky, modest buildings, perfectly ordinary reality. Unfortunately, Mrs Richards does not want reality. She wants something better. Something worthy of her expectations, her money, and her tone.

“I asked for a room with a view,” she says, unimpressed.

Basil, already stretched thin by the daily effort of pretending to be hospitable, replies with wounded pride. “That is Torquay, madam.”

For most people, the exchange would end there. For Basil Fawlty, played with surgical precision by John Cleese, this is merely the fuse being lit.

Mrs Richards calmly declares the view “not good enough.” No anger. No raised voice. Just quiet dismissal. And that is what makes it unbearable. Basil doesn’t explode immediately. He tries logic. He tries politeness. He even tries explanation. Each attempt fails, not because Mrs Richards argues back, but because she simply refuses to adjust her expectations to the world in front of her.

Then Basil does what Basil always does when reason fails him.

He imagines.

If Torquay is not enough, what would be enough? Slowly, his imagination becomes his weapon. Perhaps she was hoping to see the Sydney Opera House from her window. Or the Hanging Gardens of Babylon. Maybe a parade of wildebeest swinging majestically past the hotel, just to add a bit of excitement to the English coast.

The genius of the scene is not just the list itself, but the way it grows. Each image becomes more absurd, more impossible, more revealing. Basil isn’t really talking to Mrs Richards anymore. He’s talking to every unreasonable demand he’s ever endured. Every guest who wanted the world rearranged to suit them. Every moment where politeness was mistaken for weakness.

Mrs Richards, for her part, remains unmoved. Deaf to Basil’s rising hysteria, she treats his rant not as comedy, but as further evidence of poor service. The more animated he becomes, the calmer she appears. It’s a perfect imbalance — like watching a balloon inflate beside a pin.

Behind this unforgettable character is a real story almost as unlikely as the scene itself.

The role of Mrs Richards was written specifically for Joan Sanderson, a close friend and long-time collaborator of Cleese. Sanderson initially refused the part. She believed the character was nothing like her. Too harsh. Too rigid. Too humorless. She worried she wouldn’t understand her, let alone make her believable.

Cleese insisted.

What Sanderson eventually created was not a villain, but something far more unsettling: a person who genuinely believes she is right. Mrs Richards isn’t cruel for sport. She isn’t loud or aggressive. She simply exists in a world where other people’s efforts never quite measure up. That realism is what makes the scene endure. We’ve all met someone like her. We’ve all felt like Basil.

Years later, Sanderson reportedly said Mrs Richards was her favorite television role of her entire career. Not because she was lovable, but because she was true. A character who didn’t need to shout to dominate a room.

The scene ends, as all great Fawlty Towers moments do, not with resolution, but with damage. No one learns a lesson. No one changes. Basil survives another day. Mrs Richards remains unconvinced. And Torquay, stubbornly ordinary, stays exactly where it is.

That’s the quiet brilliance of the moment. It isn’t just a joke about a bad view. It’s a perfect portrait of expectation colliding with reality — and the fragile human being trapped in between, trying desperately not to lose his mind behind the front desk.